Celebrating Chinese culinary culture with Christopher St. Cavish.

Christopher St Cavish

If you know me you'll know I have a thing for Chinese food. When I was young my Dad would to take us to a Chinese restaurant in Norwich that was accessed via the first floor of the multi-story carpark. I’d never been to a restaurant that was just sort of in the middle of a building before. I was instantly obsessed with dumplings and 'crispy seaweed'. So much so that when I was 14 I dropped History at school to do Home Economics so I could practice making the cabbage 'seaweed' and all manner of fried beef dishes. I was recently reminded by a friend from university that I would always drag her to the Asian supermarket down in the underpass to fetch dumpling wrappers.

I spend a fair amount of time watching Youtube. It's my TV. So it was only natural that I'd encounter the channel SaintCavish filled with beautiful short documentary stories about various aspects of Chinese food culture. I’m a big proponent of what I call natural storytelling - it’s quiet, respectful, beautiful and captivating. It’s rooted in documentary and oral history techniques rather than the attention-economy industrial complex inspired dopamine-maxing social style of editing that is so prevalent today.

I got in touch with Christopher St. Cavish to ask him some questions and he gracefully obliged.

What brought you to China?

I was a chef for the first ten years of my work life. At one of my formative jobs, I worked for a big-name chef in Miami. He mostly cooked Latin food (Cental / South America, the Caribbean) but also used some Asian ingredients, which I was interested in. And I thought, I really should learn this from the source, not second-hand. At the same time, I fell in love with Hong Kong after traveling through once. So that’s where I set my sights.

So in 2005, I sold all my possessions and moved there, hoping to get a job at The Peninsula Hotel, that old grand dame, which to me represented the best there was (debatable). But my strategy of showing up, knocking on the back door, and sweet-talking the chef into offering me a job – a technique I had used with a lot of success in the US – didn’t work. I failed. Eventually, I was running out of money in Hong Kong, so I decided to go to Bangkok, which I also love, to lick my wounds and save on expenses.

On the flight from HK to BKK, I happened to sit next to an American guy, who it turned out was a chef in Bangkok, and had lots of connections in Asia. One of his contacts led me to the Shangri-La Group, which was opening a restaurant in Shanghai in its new hotel tower by an unknown French chef. The French chef interviewed me by phone, I passed, and a week later I was on a flight to Shanghai. That chef was Paul Pairet, now China’s most well-known foreign chef, and the man behind Ultraviolet, which has three Michelin stars. I had nothing to do with that; it came later, years after I bailed on Paul, and I was just a low-level kitchen peon anyways. But Paul brought me to mainland China, which I had honestly not been considering, and I’ll forever be grateful for that.

What kept you in China?

Friends, fun, the boom years, changing career to become a food writer instead of a food maker, a sense of the possibility to try new things, and a growing interest in China (after I moved here). Eventually, that interest in China won out over everything else, though my friends are still very dear to me.

Friends.

How has the food scene changed domestically since you’ve been in China?

This is a big question and a bit vague. Even just single categories of Chinese restaurants are massive industries unto themselves – hot pot, for example – and I’m not sure if you’re talking about Chinese restaurants or non-Chinese restaurants. If I have to generalize, the Chinese restaurant industry in Shanghai has gotten incredibly sophisticated and diverse. For “western” food in general, there was a boom but it’s backsliding now that China is turning inwards, and less and less new foreign chefs come to the country.

Have you noticed a shift in global perceptions of Chinese food culture?

There was a moment of interest in the 2010s, around the time Mission Street Chinese and Danny Bowien became popular. I think that opened some people’s minds to the idea that Chinese food could be so diverse and creative and move beyond the Sichuan / Hunan / Cantonese that dominated NYC, at least, since the 1970s. But I’m not so attuned to what the overseas perception of Chinese food is because I live in China, where the perception of Chinese food has changed in different ways — recognizing and appreciating more regional styles, an explosion in Chinese fine-dining, pride in Chinese ingredients (though this isn’t that new).

What is your vision for the Youtube channel?

We want to show a side of Chinese food, cuisine and culture that we don’t see done enough – something respectful of chefs and cooks and culture and history. There are some clickbaity “you won’t believe this” kind of YouTube personalities doing China food, and that’s fine, but that’s not what we’re going for. We want to engage a bit differently. We (Graeme and I) are complete converts to Chinese food (neither of us grew up with it), and we are constantly impressed and amazed by Chinese food and the culture and industry around it, and we think other people might be too. We wanna show the cool stuff we get to see but that we don’t see reflected back at us very often in the media.

I saw you've released some mahjong tiles to celebrate the recent videos? Can we expect the full 144 piece set?

That’s the goal! The dream is, once the set is complete, we give them to some aunties in Shanghai and ask them to play a game for us.

How do you select the topics and stories you want to showcase?

My criteria is either to do a new topic or a new angle on an old topic. For the first year or so of videos, we are trying to cover the most popular foods – soup dumplings, BBQ, noodles – but in our own way. I literally Googled dozens of Chinese restaurant menus from the US and went down every item and tried to think how I would approach an episode about it. That doesn’t mean we will do every item on the menu, but it does mean you can eventually expect a twist on a fried rice story.

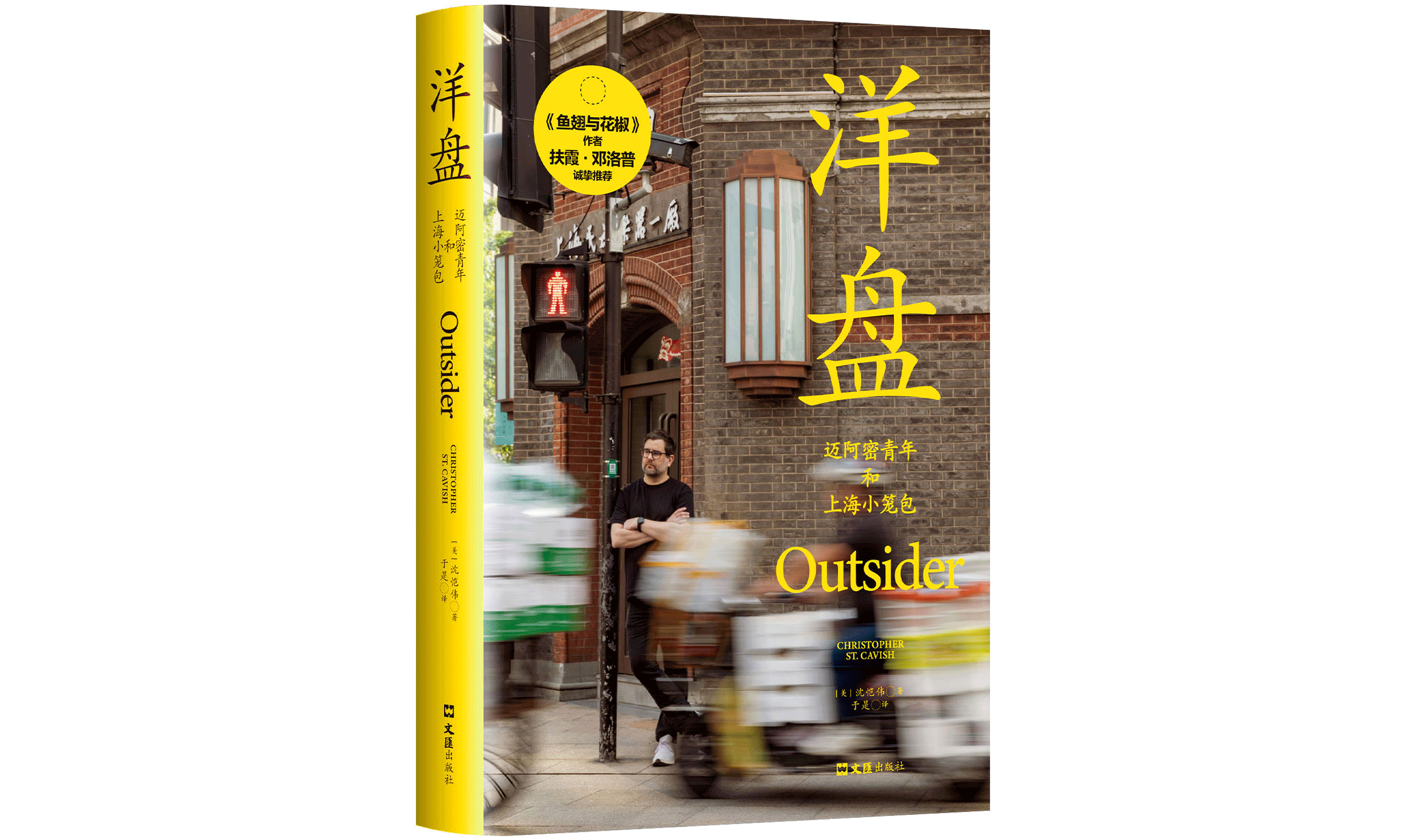

Presumably the Youtube channel is for a Western audience but your memoir was only published in Chinese - how do you decide which content is for which audience?

Yeah, that’s right. I didn’t so much decide this as it was decided for me – the book. I had begun publishing in Chinese (via translation) at the invite of a friend, and a book company liked my essays and invited me to do the book. The memoir has very little to do with food; it’s personal life and personal history type stuff. They felt young Chinese readers could relate to my story of feeling a bit in-between cultures or feeling like an outsider in some way, and so they felt it fit the Chinese market. But it’s very China-focused and expat-focused, and so I’m not sure how it would be received by a Western audience, so I’ve never pushed for it to be released in English.

I think I first encountered you through Lucas Sin - how did the two of you meet?

Lucas moved to Shanghai two years ago, and his partner, Camden Hauge, introduced us. It was pretty natural (inevitable) we’d become good friends once he was living here. There’s a little crew of us who are passionate about Chinese food but don’t fit into the Chinese restaurant industry so obviously.

Lucas & Christopher.

I feel like the two of you have a real shared passion for sympathetic storytelling and a delight in eating delicious food. I always think these were what made Anthony Bourdain so compelling. What’ s your relationship to Bourdain? Do you have a favourite episode?

I don’t have any direct relationship with him; I never met him, though he did film in China at one point. I think he did Sichuan. Bourdain’s career and episodes happened while I was living in China, and especially before YouTube, I just didn’t have access to international TV and programs, so I’m only familiar with him in retrospect, by watching old YouTube episodes. I know his books better, especially the first one, which really resonated with me as a young restaurant cook. He was kind of the first one to stand up for restaurant kitchen culture, which is def a thing, and make it public. I love that fucked-up culture the same way he did.

I’m a bit of a hermit in terms of media consumption. I don’t have a TV , I don’t have Netflix or any of the others, I don’t stream or download TV or movies. I watch YouTube but usually not food stuff. I guess I feel I’m a little too impressionable and I don’t want to be influenced. Having my own voice is important to me, in whatever media I’m operating in (written, video, research), so I try to keep some distance from a lot of popular culture. I know that sounds miserable and a big buzzkill, but for me, it’s just normal and I’m not miserable at all. Weird maybe but not miserable.

When I moved to China in 2005, I was cut off from most international pop culture, or I had to fight to be an active consumer of it. I wasn’t surrounded by English-language TV , radio, movies, all this stuff that is constantly blaring when you’re living in the US or Europe. And I found it really refreshing. So I just went with it. Of course, I have the internet, and I can access all the “blocked” sites, but… I don’t know. Having some remove from it all feels healthy to me and keeps me happy.

Who else do you admire / respect in terms of food storytelling?

I think Lucas (Sin) is my favorite right now. Fuchsia Dunlop is of course the big star for our field and she’s great. I like stories that are not directly about food but touch on bigger issues, like Ian Urbina’s 2019 book The Outlaw Ocean or Dan Barber’s The Third Plate, though that one is ten years old now. I think Eater and Bon Appetit have done some great stuff on YouTube in the past year that I’ve enjoyed. But again, I’m kind of a random consumer of media. I don’t keep up on it too much unless I’m doing specific research.

I feel like a lot of Chinese dishes require equipment that you don’t find in modern / western kitchens. Do you cook much at home and if so what kind of dishes?

I’m not sure I agree with the first half of that question. I think Chinese food is probably one of the least equipment-heavy cuisines: a wok and a knife are really the only necessities. And even then, I’ve made plenty of Chinese food at home using a saute pan (don’t tell anyone). A gas range is nice but there are plenty of induction woks in China too. A steamer is high on the list of equipment too. But really, there’s not the ecosystem of task-specific cookware in Chinese cuisine as there is for non-Chinese food, in my opinion.

I alternate between an addiction to the convenience of delivery (an embarrassing but true fact of life in modern Shanghai, where it's often cheaper than even going to the restaurant) and cooking for myself. I cook Chinese food at home if I'm trying to understand a dish or a technique or a flavor combination but otherwise I tend to eat out and leave it to the professionals. Going out, for me, is education. No point to do it myself when there are so many teachers out there.

I’m a big fan of noodle dishes - particularly the Dan Dan / Chonqing axis. What are your favourite noodle dishes? Are there any lesser known bowls you recommend or interesting regional variations on popular classics?

I am writing an entire book on the subject (two, actually, because it’s so big). Lanzhou beef noodles (niu rou mian, if you’re in Lanzhou; or just the bastardized and shortened “la mian” if you’re not) are my biggest noodle obsession. Not just for the flavor, which is quite different (and much much better) in Lanzhou, but for the history, science, geography, sociology, technique… it has everything. For me, it’s the king.

Sichuan noodles are easy to love, and rightly so. Yibin ranmian (“kindling” noodles from Yibin) are probably not seen as much as Dan Dan Mian but just as good. In Shanghai, Cong You Ban Mian (spring onion oil noodles) are essential. Suzhou is my favorite noodle city in east China. It’s only a 90 minute drive from downtown Shanghai but it has a different (and I dare say better) noodle culture than Shanghai. It’s still quite seasonal, with duck, crab, shrimp and braised pork all making their way into noodles in some form (not together). I have a ppt I commissioned with noodles from around China, for research. It’s 100 noodles long and far from comprehensive. I could go on…

You recently brought 3 italian pasta chefs to China to explore noodle culture. What was the most surprising / rewarding aspects of that experience?

The most surprising part of the Italians' trip to Shanxi was in the first restaurant, when we captured the noodle chef who has been there for five decades saying that "before, kitchens used to be 'i don't show you, you don't show me'. but now that's changing, and we're open to share." that was a really touching moment that only could have happened chef-to-chef. the noodle chef had never been in any media or anything before, and he only agreed to talk to us because of the Italian chefs. the most rewarding was going to the noodle program at the vocational school, and just watching the small interactions and reactions between the professors, the Italians, and the students.

You've dug deep into things like roast pork, dumplings and noodles - what new rabbit holes have you sent yourself down?

My yard is littered with rabbit holes. The noodle one is particularly broad and deep, with many sub-branches. It's also going to become a book, so i've been spending a lot of time on that subject.